SupremePunk #040

Сhildless Father

This Punk is inspired by CryptoPunk #3133 and artworks of Malevich. This work is one of a series of paintings that reinterpret a series of portraits of peasants by Malevich. Just like Kazimir Malevich, these Punks were created at different times (which is why they come in different drops), are made in different styles but contain similar ideas. Kazimir Malevich was born and raised in a rather poor family and spent his childhood years in the villages among the peasants. This greatly influenced his style, and a lot of scenes from the life of peasants are reflected in his paintings. Over time, he became familiar with life in the countryside and the character of the peasants. In them he saw the accumulated strength of a vast country, which began to disintegrate before his eyes. In these people he discerned a simplicity and sincerity that dominated everything else. He especially valued these qualities and tried to emulate them in his life.

K. Malevich — Mower, 1913

The first category are portraits "with a face". These are some of the first works in Malevich's "peasant" cycles. Here the peasantry in his understanding is still naive and frivolous. He portrays them at work, trying new instrumental experiments. Many of the works are made in the style of iconography - the traditional Russian style. This ease with which he places the peasants in different places in his work also correlates with his attitude toward the peasantry itself. For him, their fate is still utopian - he believes in their chosenness and unpretentiousness - only the peasants, in his opinion, combined labor and laziness, which do not interfere, but complement each other. This allows peasants to engage in painting and be in constant cyclical labor at the same time.

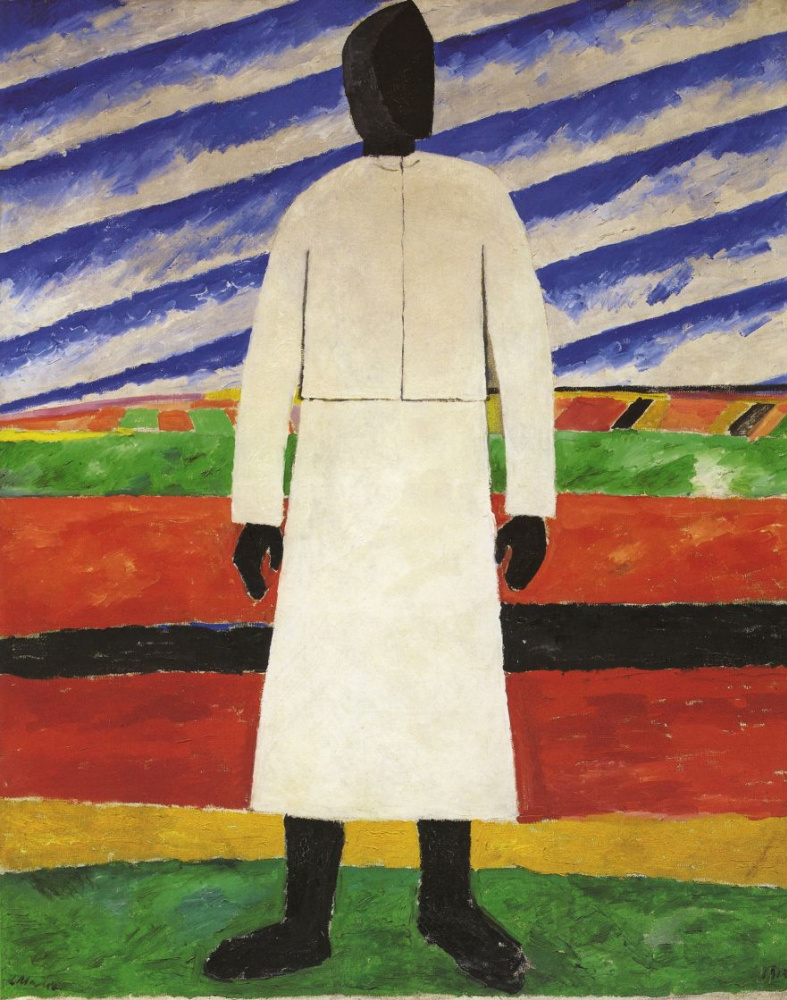

K. Malevich — The woman, 1930

The second type is the "faceless" portraits. This series of works belongs to the post-revolutionary period. For the first time, the common people showed that they are able to rebel and independently manifest their will. At this time the peasants became a significant figure in the history of the country, but as a consequence, the ruling circles wanted to curb and subdue the entire class. According to Malevich's figurative system of texts, one of the interpretations of the absence of countenances is the refusal of art to take on the temporary appearance of any leader or ideology. The heroes of Malevich's second peasant cycle are passive - but in their passivity there is stability, there is inner resistance. Malevich, without quite articulating it himself, became an advocate of art for the peasant way of life, which was sacrificed to the principles of Stalinist efficiency and the tasks of industrialization. Here one can sense the author's desire to portray a certain transcendental experience of otherness, filtered through the filter of human suffering, loneliness in an empty, unfriendly and open to the cosmic cold.

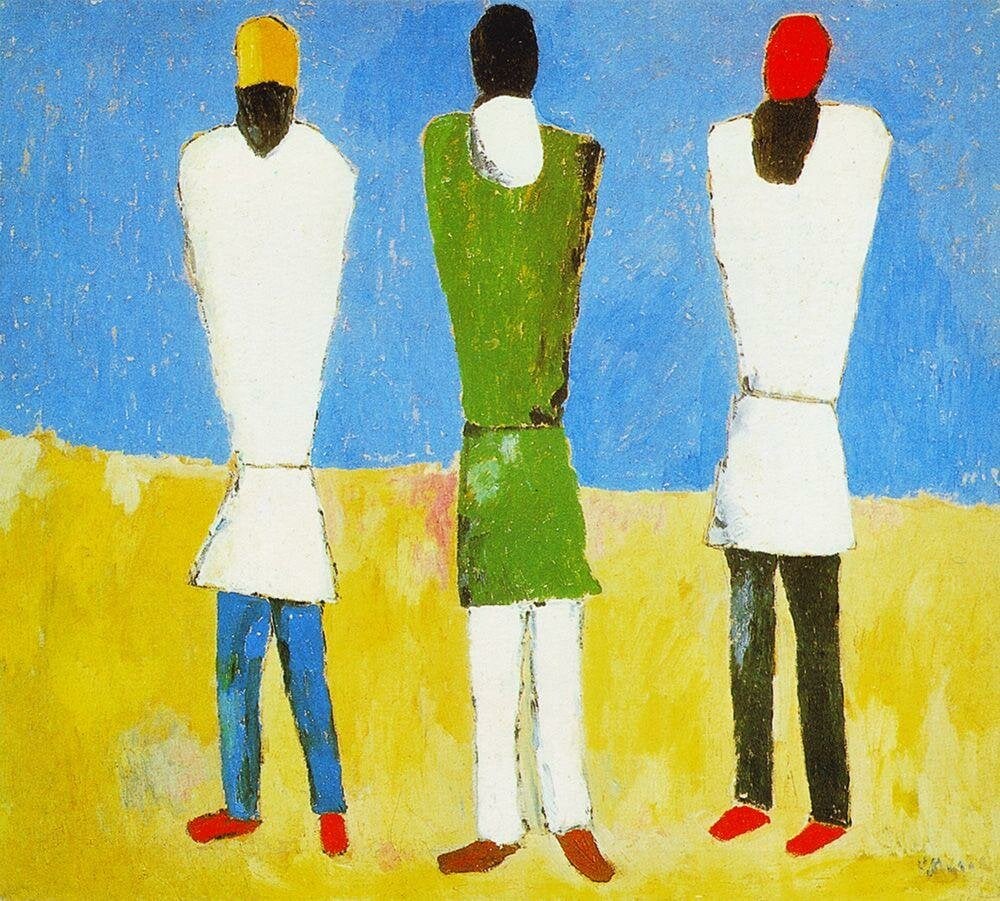

K. Malevich — Peasants, 1932

And the last type is the "armless", which also belongs to the post-revolutionary period, but it is distinguished by its greater "obscurity" by the artist. And if facelessness can also be interpreted as a symbol of the mystery of man's future and not yet fully determined fate, the absence of hands ("Peasants", 1932) is a tragic premonition of Malevich, which from that time already began to translate into reality. In this period the peasants are depicted not only outside work, but they do not even have the opportunity to do so, because the author has taken away from them the most important thing for a peasant - their hands. It must be understood that in that era the peasants' entire product came solely from manual labor. Therefore, the absence of hands shows the impending helplessness of an entire class and extinction against a background of an already barren and monotonous land.

Today, Malevich's second peasant cycle (the second and third types) can be interpreted as one of the strongest images of the passive resistance of the peasantry in the 1930s, during forced collectivization. But Malevich's images of the peasants are not simply suffering. They also contain a dimension of utopia, a utopia of exodus from history. Looking at Malevich's peasants, one can never distinguish between anti-utopia and utopia, between the image of violence and the image of freedom. In this tension lies the aesthetic power of the peasant cycle.

Buy

Gallery:

CryptoPunk #3133 that has been taken as a base

Your transaction is in progress

You have connected to the wrong network

Transaction is successful!